Just before Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24th, the Association of Ukrainian Human Rights Monitors on Law Enforcement (Association UMDPL) called for evacuation plans that took into account the people in Ukrainian prisons. The Association detailed abuses that had come out of previous Russian incursions into the Donetsk region: prison staff evacuating without giving any information to incarcerated people, leaving them to go without medical treatment, face shelling, and flee – in some cases into minefields or forced labor for Russian-backed militias.

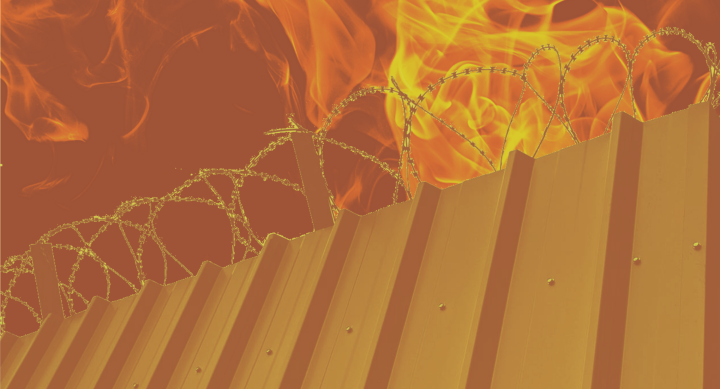

Now, as Russian forces have attacked Ukrainian cities and towns, increasingly targeting civilian areas, at least five Ukrainian prisons have been shelled. Some 33 Ukrainian prisons are in active conflict zones, and some of these facilities are “in crisis,” struggling to provide water, heat, electricity, and communications.

These outcomes should serve as a sobering reminder that people who are incarcerated cannot choose to evacuate, even when conditions are life-threatening.

We should also remember that – as much as the war in Ukraine has underscored the reality of prison evacuation in times of crisis – these are not only problems that arise during war. Shelling is not the only reason to leave an area, and armed conflict is not the only time that we have an obligation to ensure the safety of the very people whose ability to flee danger we have taken away.

Closer to home, this has been on my mind as wildfires burned more than 108,000 acres west of Dallas and led to the evacuation of 19,000 people near Boulder, Colorado in March, and as another 3,000 acres continue to burn near San Antonio. “EVACUATE IMMEDIATELY!!” read the tweet from Erath County, Texas. What about those who do not get to make that choice?

Fortunately, no Texas prisons seem to have been at risk from these fires – but other prisons have not always been so lucky, and that risk is only growing. Callousness towards people who are incarcerated greatly magnifies that risk. As reported by The Intercept, people incarcerated near a growing wildfire in California recounted guards telling them that “you effers are going to stay in your cell” even if the prison was on fire. In some cases, as with Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans and Hurricane Irene in New York, impending disasters have revealed that prisons and jails have not contemplated disaster risks enough to have plans for a theoretical evacuation. Even when evacuations have occurred, poor planning has sometimes led to overcrowding and further abuses like the indiscriminate use of pepper spray on evacuees.

Fleeing – leaving our homes, possessions, shelter – is not a step any of us ever want to take. But we all deserve to have the choice about whether to do so.

With wildfires, drought, extreme temperatures, hurricanes, and flooding all becoming more frequent and harder to predict, this is not an issue we can afford to ignore. Just as the Association UMDPL pointed out in Ukraine, the answer here is planning that centers both the humanity of people who are incarcerated and the responsibility of the state to protect the people whose freedom to evacuate it has taken away.

Fleeing – leaving our homes, possessions, shelter – is not a step any of us ever want to take. But we all deserve to have the choice about whether to do so. When evacuating is the last choice left on the table, it is also, generally, the best choice. We cannot leave people who are incarcerated without that option: prisons and jails must have clear and humane evacuation plans, and must use them when disasters threaten.

"Degree of Civilization” is the blog of the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab, its title adapted from Dostoyevsky’s famous quote, "The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” Our blog posts will explore and analyze the dehumanizing and dangerous conditions in our nation’s prisons and jails and the critical need for effective independent oversight and meaningful data about what’s happening behind the walls. We’ll be commenting on recent news and developments; analyzing data that highlights trends that affect the safety and health of the people who live and work in correctional facilities; and reflecting on the lived experiences of people who are incarcerated. The entire PJIL team will be contributing to the blog, so you are sure to hear different voices and approaches to these issues.

Author

-

Joshua McClain

Josh McClain graduated in 2025 with a joint degree from Texas Law and a master's degree from the LBJ School of Public Affairs. Prior to graduate school, Josh worked with Legal Aid of North Carolina, a civil legal services provider, focusing mainly on long-term disaster relief. Over the course of graduate school, Josh has worked with Texas RioGrande Legal Aid and the Southern Environmental Law Center, in addition to holding a number of research-assistant and teaching-assistant positions at Texas Law. For PJIL, Josh provided research and produced written materials to support some of the lab's portfolio of projects, including the National Resource Center for Correctional Oversight and the Louisiana Jail Standards Project. Josh is currently focused primarily on research into environmental conditions in Texas prisons and continues to contribute to the NRCCO project.

Key Words

evacuation

health

natural disaster

safety